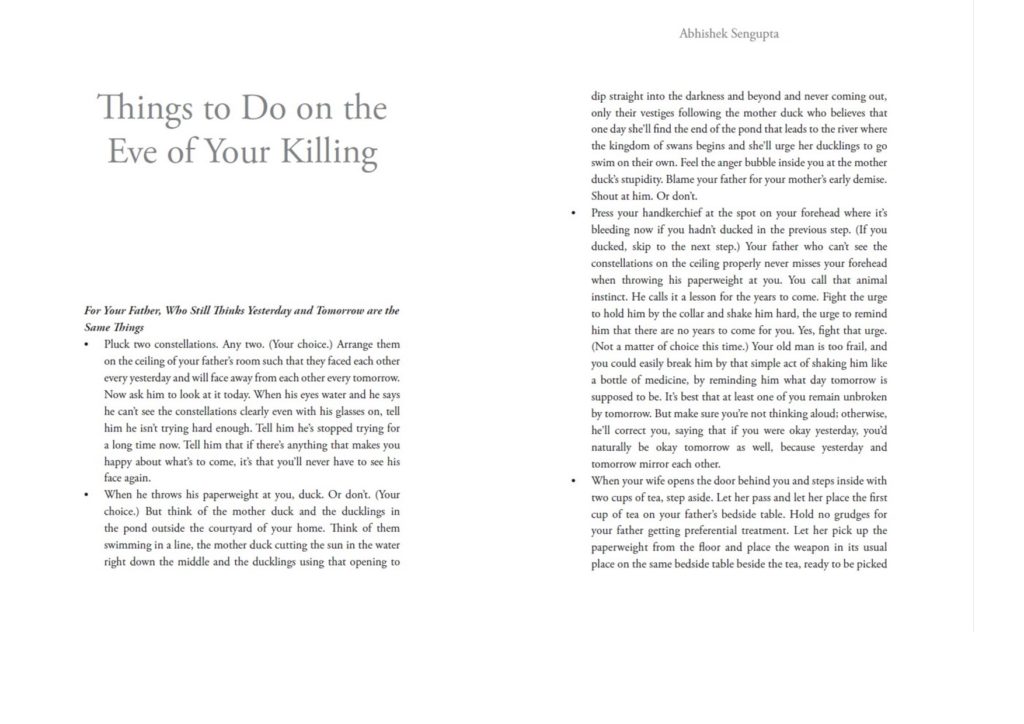

The 2023 Bristol Short Story Prize was won by Abhishek Sengupta who lives in Kolkata. Abhishek won with his story, Things to Do on the Eve of Your Killing.

We took the opportunity to ask Abhishek about his recent triumph, how his winning story came together and his writing in general. Big thanks to him for giving up his time to provide some intriguing and thought-provoking answers.

What did you think when you were announced as the winner of the 2023 Bristol Short Story Prize?

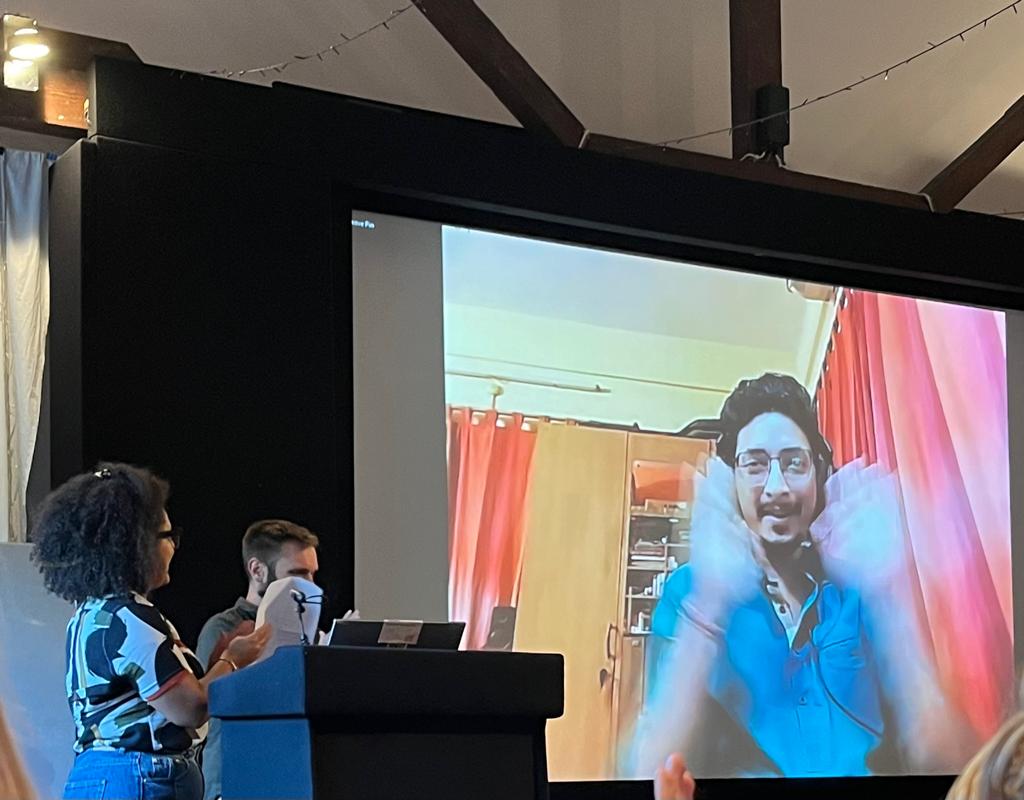

I was about to fall off my chair. Literally so. That announcement was so unexpected. I was attending the award ceremony purely out of curiosity about how such an event associated with a Prize as reputed as yours is conducted. I considered myself extremely lucky that my story could make it to the shortlist. Even when I was emailed, as a shortlisted writer, about reading an excerpt if I won, I took it too casually. I never even opened the actual story to give it a thought as to how I was going to present it, let alone rehearse my reading. So, yes, the announcement caught me completely off-guard. And then it dawned on me that now I need to read an excerpt too, and I was frightened I would do a spectacularly poor job at that. Thankfully, I had written, directed, and performed a few radio plays with choreography in front of a live audience (yes, I know that sounds odd in writing, but yes there were dancers in a radio play performed live!) apart from doing some regular stage plays, although those were in my mother tongue, Bengali. So, I thought I’d treat this reading too as a radio play. In the end, I’m glad I could keep them (and you) engaged for those few prolonged minutes. My heartfelt thanks to the esteemed judges, the organisers, my fellow nominees, and the audience in general for their patience and steadfast perseverance to sit through something so experimental in nature.

Your winning story takes the form of a kind of to-do list. Did it start out that way? Why did you select that form for the story?

Yes, that to-do list was always a given since this is one of those stories that began with its title: Things to Do on the Eve of Your Killing. At its very inception, I had been pondering what would you do if you knew you were going to not only die but be killed tomorrow. My kneejerk reaction to that concept was (and because I habitually converse with myself out aloud at such times): “This one’s just another one of your absurd, irrational ideas, Abhishek. How would a person know that they are going to be killed tomorrow? And even if we accept, for argument’s sake, that they do, the only thing they’d do on the eve is try to flee. You have no need for an entire to-do list to get there. It’s an open-and-shut case.” But then, immediately I loved that very challenge of there not even being the scope of a story in that premise without the protagonist making a run for their life. So, basically, I embarked on a journey to prove myself wrong. And the form had to stay just as I had initially conceived it because now, I was making a show of the sceptic in me (the other Abhishek) that yes, there can be a perfectly rational story with that title.

How many drafts do you typically go through before you are satisfied with a story?

Oh, number is a poor measure of revisions since the term revision itself is relative. For example, I’ve often found that adding or changing a word or two in a (let’s say) 3000-word story could change the core concept of interpretation of that story for a reader. So, if I add that word (or two), would you call it a new draft? And if your answer to that question is yes, how am I to judge which of those two-word changes qualify to be termed as a new draft and be counted thus?

Lately, quite a few of my stories have decided they’d present themselves as a jigsaw puzzle in front of the audience. So, I just let them be, let them do their thing (you know, the entire nature vs. nurture argument rigmarole). But since such a thing presupposes active participation on the reader’s part to put those pieces together, it becomes my responsibility to make sure that I’m designing the pieces such that the readers could go on connecting the dots. And this one is a delicate dance that calls for a patient finetuning. So, although I can’t quote you a number, I can tell you this: when it’s a puzzle piece, the creator needs to invest their time so the readers could get an optimal return on investment for their precious time. I’m revising as long as I haven’t got that ROI right. Sometimes, everything magically fits after a few attempts; other times, it’s pure arithmetic. Algebra, even. (Oh, the horror!)

You use the second person point of view for Things to Do on the Eve of Your Killing. What did that technique enable you to achieve in the writing of the story?

It did enable me to achieve something extremely important for this story. But to start off, it wasn’t an easy decision. You see, as a reader, I’m generally quite critical about second person POVs. This can be partly because of a personal notion I harbour that tells that the second person POV is a scarce resource that must be used responsibly and conscientiously. I prefer a first and third person POV wherever possible because I feel it makes the reading more seamless, less of an effort. A second person POV has an odd knack of drawing attention to itself and taking parts of that focus away from the character and the plot. The form rather than the matter. As soon as I conceived this as a to-do list, I knew this one had to be a second person narrative to be even granted an entry in the pearly gates of to-do lists. So, my first preoccupation right from the beginning was to make sure that the form enhanced the matter rather than marred it.

But there’s a second layer to the second person POV in this story. And this is where things get a lot murkier. To explain this, let me start with an example of a second person POV: “On the long-forgotten table, you find a piece of paper. It’s oddly blank. You pick it up, turn it overleaf. Nothing’s scribbled on either side, but one side feels emptier than the other. You’re sure about that.” In this example, the second person POV is aiding the reader in internalising the description of an experience. And that is the usual and rightful job of a second person POV in a story. In the story I was then about to write as a to-do list, the POV had a different task: it was to instruct the readers to act on something rather than describe an intimate perspective. A commonplace reaction to a reader being instructed in a story is don’t-tell-me-what-to-do. So, this story, even before it started, had that additional responsibility to shoulder: to overcome the reader’s reluctance on being instructed to act. This turned out to be a rather big learning experience for me as a writer, because essentially, by that choice of form, I was building a house of cards: one wrong move, and the entire thing would have come tumbling down. Yet, I realised, every time I got it right, that instruction-manual mode enabled me to reach a hitherto unknown emotional core of the characters by the sheer rawness of its unfiltered approach. So, was chalking the exact path to get there difficult? Yes. But writing it was an immensely cathartic experience. If anyone’s liking this story, they are most probably sharing a piece of that cathartic experience with me. This couldn’t have been possible without that authoritative-yet-immensely-vulnerable voice.

What do you want readers to take from your winning story?

My personal goal as a writer has always been to bring to light stories that aren’t getting told in English literature, perspectives that are still left unexplored as far as the world audience is concerned. Sometimes, those stories spring from my very own backyard; at other times, they are from other parts of the world or about patterns found in various parts of the world taken together but yet untold. In this story, the backdrop is plucked from my backyard garden but set in a historical timeline. I was trying to make history sound modern, because even though the finer details have changed, the experience continues to persist. The experiences of the characters in this story may as well be connected with a straight line to the real-life experience of a person from this era (and I wish it wasn’t that way, that what I wrote was sheer fiction in our current timeline). If anything, I want my readers to naturally acknowledge this fact. Sometimes, our acceptance itself is a healing experience for someone else, especially when they’re piled under a debris of heavier, chunkier pieces of news, and they reach out, but no one notices their hand or pulls them out so they may breathe again, howsoever toxic the air may be. Breathing can be enough at times.

Looking at short stories in more general terms, what possibilities do you think the form offers to writers?

The possibilities are infinite, if you step out of their comfort zone and stare outside your window. And when you do that, those possibilities become more than infinite. They become hope even if you’re writing about the most depressive events and experiences. There are times when people are feeling down burdened by a chaotic daily existence, fighting their demons. I’ve often seen a short story give them a miraculous release. You never know how the fictional account of an experience despite being diametrically different from their own experiences may yet touch them more intimately than if someone had recreated their own personal battles on paper. And that is the power of a short story. Because of its perfect length, it’s there right when you need it. No delays. No holdups. And if you can touch people’s lives when they need it most, when others are ignoring their struggles, I don’t think a writer can ask for a better possibility for their short stories.

When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

When I was fourteen and realised that if I oil painted a tree on paper, I had to subtitle it as “a tree” for others to understand. If I didn’t write, how else would I have painted?

Which writers have had the biggest influence on you?

Milan Kundera, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Arundhati Roy. But when it comes to my writing, I draw influences from other sources more than writing itself (as odd as it may sound). An avid cinephile, films from around the globe have been a great inspiration in my writing. Filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Theo Angelopoulos, Emir Kusturica, and Asghar Farhadi have often influenced my plotting and characterisation. And then, music too: songs by George Michael and Lucky Ali, and scores by two contemporary Greek composers (both female), Eleni Karaindrou and Evanthia Reboutsika. I don’t think I would have been writing anything of the sort had it not been for their music.

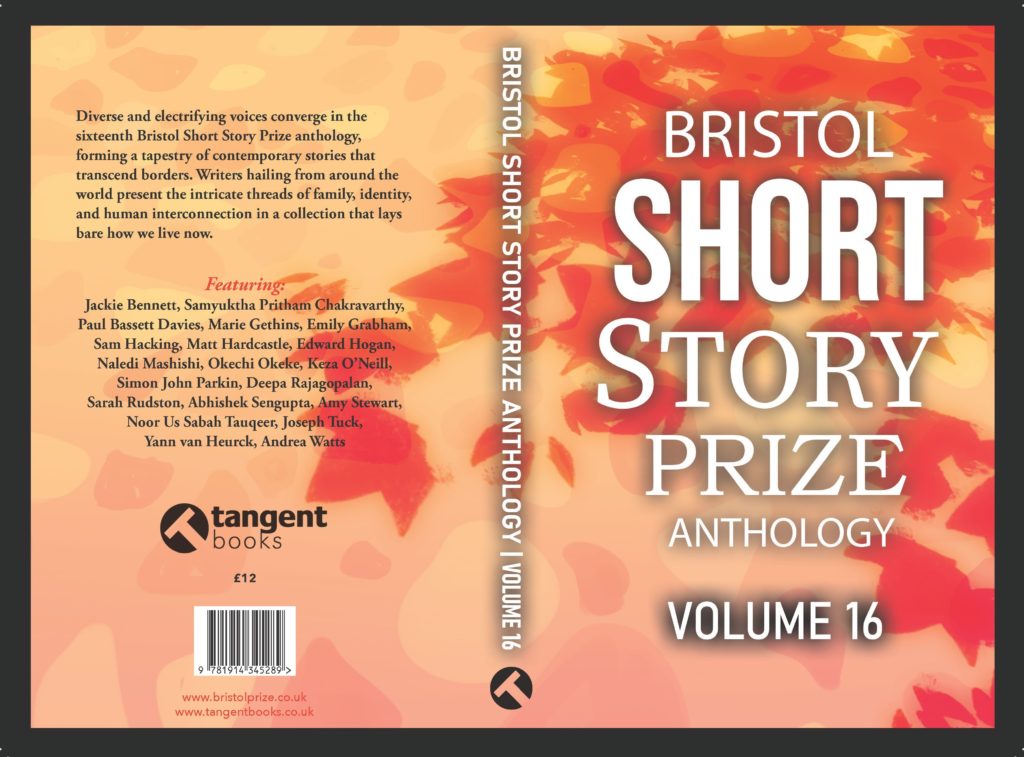

Abhishek’s winning story, Things to Do on the Eve of Your Killing, is available in our latest anthology direct from publisher, Tangent Books, or via bookshops.